“Invisibility is an unnatural disaster”: Why funding the 2020 Census matters for Pacific Islanders

Published in Urban Wire on

Data sheds a light on challenges faced by distinct AAPI groups and how these groups strengthen their communities

On Tuesday, the director of the US Census Bureau, John H. Thompson, announced his intent to resign at the end of June instead of at the end of the year. His decision comes at a time of struggle for the Census Bureau, as it faces serious challenges with funding the decennial 2020 Census.

This news follows last week’s joint statement from several Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI)–led organizations on Census data collection and reporting standards. In a two-month mobilization effort, they collected over 3,600 public comments from 47 states and US territories urging the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to update its standards to include more detailed data for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders.

The term “Asian or Pacific Islander” first appeared in the 1990 decennial Census survey, but in 1997, the OMB issued a directive that the US government disaggregate the data further into “Asian” and “Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander”—and for good reason. The catchall category “AAPI” is popular among researchers and race equity advocates, but can conflate the identities and issues of two distinct groups: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

Unlike many Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders’ history in the United States “has been one of colonial contact and conquest, with the growth of plantation economies and the US military power in the Pacific playing important roles.” Although Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders often advocate collectively for common goals, this should not preclude policymakers from serving them as distinct communities with specific needs.

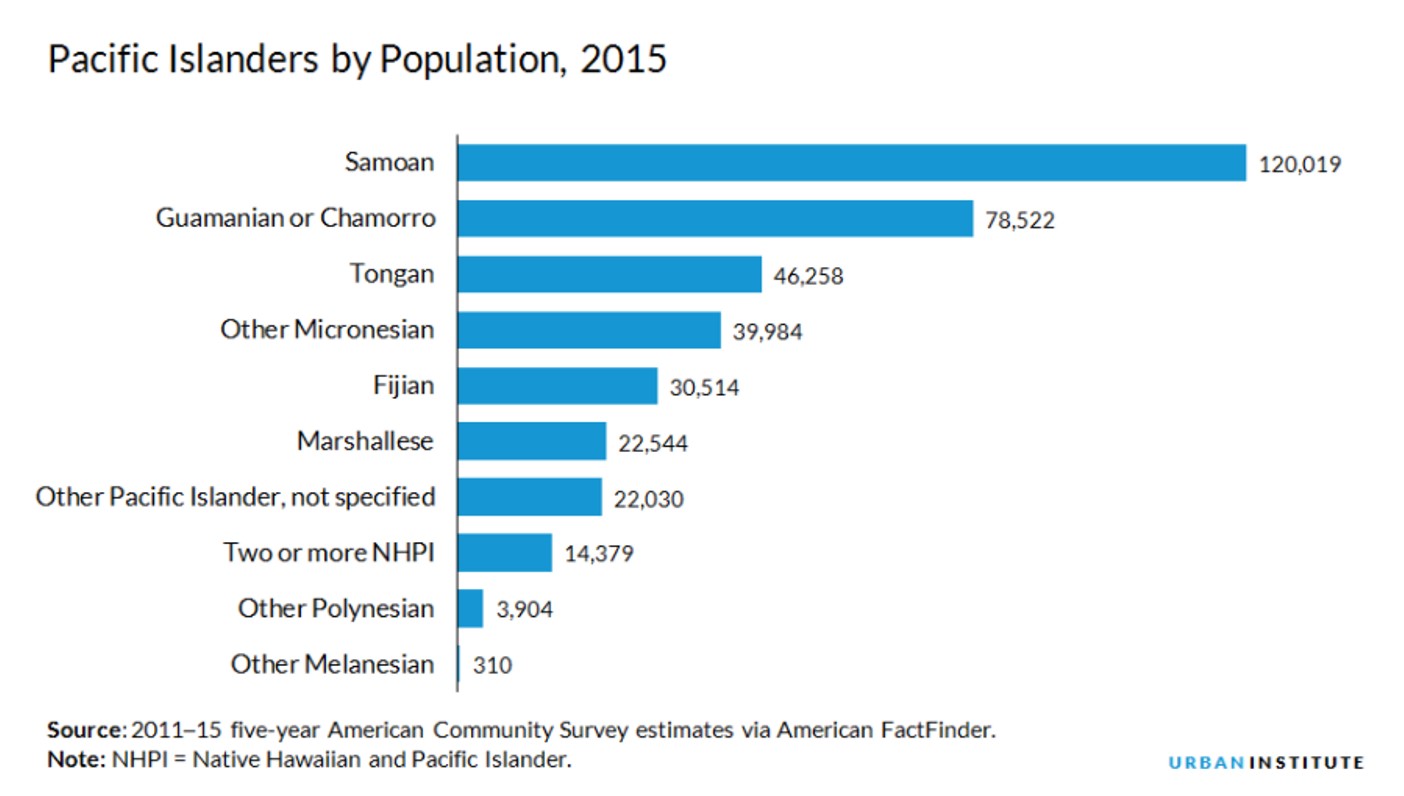

“Pacific Islanders” refer to communities whose origins are indigenous to Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia. These groupings are made up of nearly 20 different communities, each with its own language, culture, and traditions: Chamorro, Chuukese, Fijian, Marshallese, Palauan, Samoan, Tahitian, Tongan, and others. According to American Community Survey estimates, their combined population is just under 379,000. The largest Pacific Islander communities live in Alaska, California, Hawaii, Utah, and Washington.

Because the Pacific Islander population is 45 times smaller than the Asian American population, using “Asian American” and “Asian Pacific Islander” interchangeably is functionally erasure.

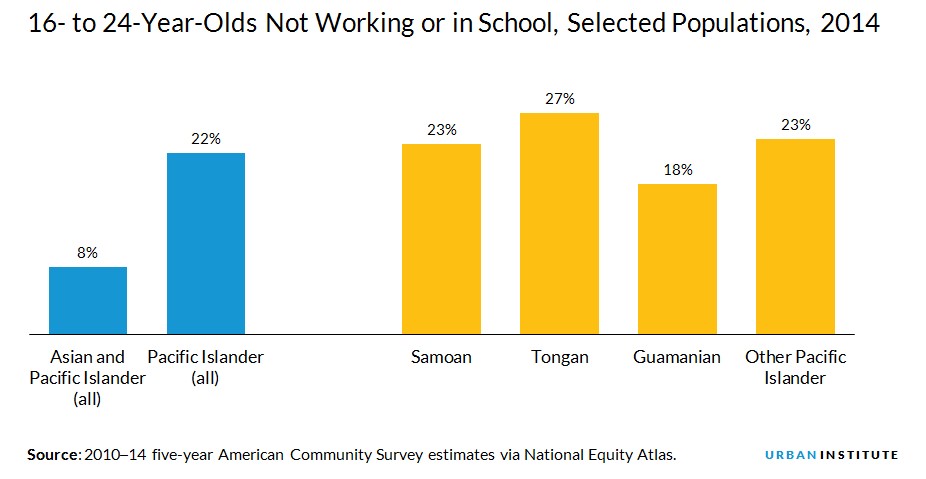

For example, in 2014, the aggregate share of AAPI youth ages 16 to 24 who were not in school or working was 8 percent. If we break down that statistic, we see that the share of “opportunity youth” in Pacific Islander communities is much higher.

The way we collect and report data for Pacific Islanders can severely limit opportunities in their communities. Even though only 14 percent of Pacific Islanders had a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2014 (compared with 58 percent of East Asians and 73 percent of South Asians), they receive proportionally less in financial aid and scholarships.

Aggregate AAPI statistics sometimes communicate that Pacific Islanders are not necessarily underrepresented or disadvantaged in higher education. Disaggregated data, on the other hand, reveal both where Pacific Islanders face barriers and where they celebrate successes.

As the US population grows and shifts, funding the 2020 Census will be critical for organizations to run equitable programs, for policymakers to find evidence-based solutions, and for the public to access timely and relevant data on the characteristics of their changing communities. As Director Thompson testified at his 2013 nomination hearing, everyone benefits from collecting and reporting accurate information.

Decisions to disaggregate data or not—and the funding allocations required to make that possible—have real consequences for underserved populations. If Pacific Islanders are not counted as communities distinct from Asian American populations, they will be at risk of being overlooked in national conversations on higher education and much more.

When Congress decides on the Census budget, members should count the cost of excluding Pacific Islander voices and struggles.

Despite being the fastest-growing population in the United States, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) are often overlooked or reported as a monolith in research on racial and ethnic disparities. Representation matters—and that’s especially true in policy research, where “invisibility is an unnatural disaster” (Mitsuye Yamada). Aggregate statistics obscure communities’ contributions and needs, so data disaggregated by ethnic origin are needed to change stereotypical narratives around AAPIs in every area of policy research.